Disclaimer: Viewers of this material should review the information contained within it with appropriate medical and legal counsel and make their own determinations as to relevance to their particular practice setting and compliance with state and federal laws and regulations. The APSF has used its best efforts to provide accurate information. However, this material is provided only for informational purposes and does not constitute medical or legal advice. This response also should not be construed as representing APSF endorsement or policy (unless otherwise stated), making clinical recommendations, or substituting for the judgment of a physician and consultation with independent legal counsel.

The need for Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT), which is life-saving for many patients with refractory psychosis and/or major depression,1 continues throughout the pandemic. Given the penetrance of COVID-19 in the New York metropolitan area, the Weill Cornell Medicine- New York Presbyterian Hospital Westchester Behavioral Health Center departments of Anesthesiology and Psychiatry collaborated to develop guidance on how to safely perform urgent ECT during the COVID-19 pandemic.

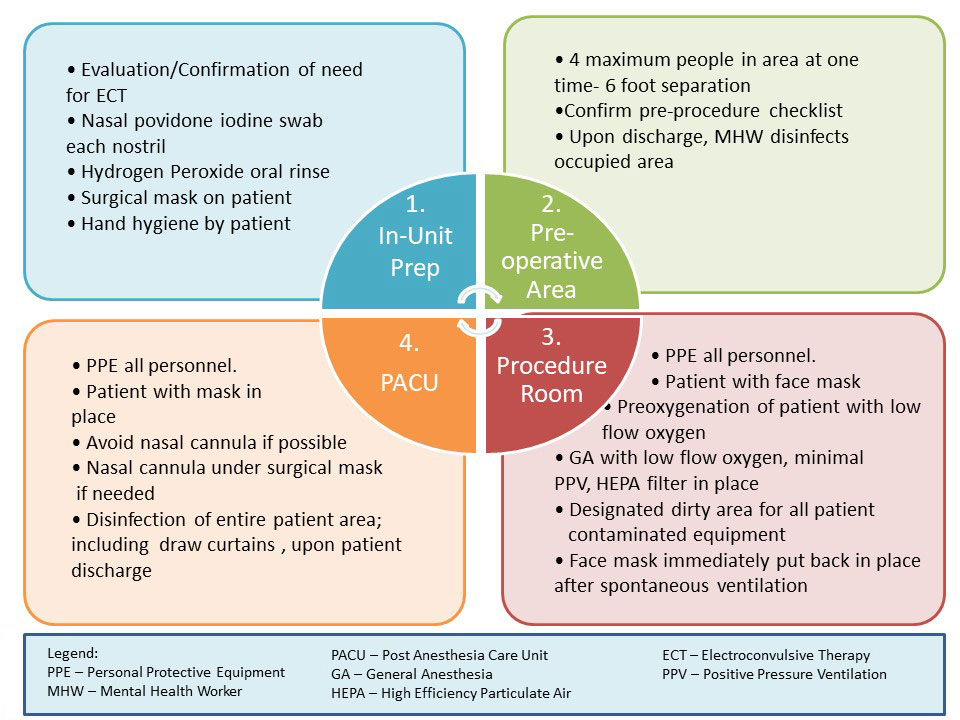

Previously, 8-10 patients per day (average 2 per hour) were treated on a thrice weekly schedule. Since the Westchester Behavioral Center absorbed all inpatients from the main Weill Cornell campus during the surge, the volume increased to as high as 16 patients per day. Early guidance regarding airway management in COVID-19 patients recommended rapid sequence intubation and avoidance of mask ventilation in order to reduce the risk of droplet spread and aerosolization of virus. 3 The Department of Anesthesiology decided against repeated intubation and extubation or insertion and removal of supraglottic devices for ECT treatment as these procedures could potentially result in a greater risk of aerosolization of particles compared with mask ventilation performed with a tight mask fit, utilizing a low flow of oxygen (2-4 liters/minute) and generating low tidal volumes of ideally 2-3 cc/kg. Recognizing that all possible airway management techniques for ECT are aerosolizing, several steps were taken to mitigate the risk for patients and staff. First, all personnel in the procedure suite were to wear N-95 respirators at all times. Intensive training in appropriate PPE donning and doffing was established. Second, air exchange in the procedure room was enhanced by installation of a portable negative pressure HVAC (heating ventilation air conditioning) system. Finally, an attempt to reduce potential nasopharyngeal viral burden was established. Povidone iodine nasal swabs and either 1.0 – 1.5% peroxide or 0.2% povidone mouth rinse are recommended in the oral surgery literature due to the susceptibility of SARS CoV-2 to oxidizing agents.4,5 Chlorhexidine is not as effective.6 Our comprehensive protocol is illustrated in Figure 1.

A pre-procedure sample checklist (Figure 2) is utilized to ensure proper screening and patient preparation. The patient is brought to the ECT treatment suite by a mental health worker (MHW). Refer to Figure 3 for procedural room events. Of note, a Jackson-Reese circuit is used for oxygen delivery due to the ease of spontaneous ventilation compared with an Ambu® bag. A High Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filter at the immediate mask outlet is used to contain droplets within the mask and limit aerosolization. Mask ventilation is performed only if necessary and one anesthesia provider ensures proper mask fit while the other “squeezes” the bag of the circuit. Accepting that mask ventilation is aerosolizing, all personnel in the procedure suite wear PPE including N- 95, welder mask, impermeable gown and double gloves. After resumption of spontaneous ventilation and emergence, the patient is brought to the PACU. Decontamination of the ECT suite is illustrated in Figure 4.

Several challenges have been encountered in implementing this ECT process. Because of the uncertainty of the air change per hour and the need to accommodate up to 16 patients per day at the onset of the surge, it was necessary to have all personnel wear N 95 masks throughout the day. In addition, since availability of HEPA filters for mask ventilation was inconsistent, high quality paper filter Heat and Moisture Exchange (HME) occasionally were used in order to reduce and/or contain viral droplets into the mask. Additionally, two anesthesia providers were available to ensure complete mask fit if positive pressure ventilation was employed, as well as ensuring proper donning and doffing of PPE. This significantly differs from the past, where anesthesia for ECT had been performed by a single anesthesia professional. An additional challenge is preventing “community spread” within the institution. In fact, a few patients developed COVID-19 symptoms and tested positive during their treatment. Infection Prevention and Control analysis determined this to be unrelated to timing or sequence of ECT treatments.

The current policy requires all patients to undergo SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing on admission, and all ECT patients are tested weekly for surveillance. All psychiatric inpatients are required to wear masks and practice social distancing. There have been no reported incidents of patient distress or refusal of the pre-procedure nasopharyngeal hygiene, which is much less invasive than the weekly PCR testing. This protocol was implemented prior to publication of the SNACC recommendations. The team has not experienced issues with secretions and felt that adding a preprocedure IM injection would cause staff and patient dissatisfaction. To date (May 29, 2020), we have performed over 300 treatments utilizing this protocol and our treatment team remains asymptomatic. Future decisions regarding the need for and frequency of surveillance testing of inpatients as well as determining at what time COVID-19+ patients may return to the ECT suite to continue their treatment will be reached via collaboration among the departments of Anesthesiology, Psychiatry and Infection Prevention and Control. Please refer to ASA website7 for CDC recommendations for assessing when it is appropriate for patients to have procedures after testing positive for COVID-19.

Janine Limoncelli, MD is an assistant professor of Anesthesiology and Director of Anesthesia of Operating Rooms at David H. Koch Center at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Tambudzai Marino, DNP, CRNA is a nurse anesthetist at NewYork Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Roy Smetana, MD is assistant professor of Clinical Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Pablo Sanchez-Barranco, MD is assistant clinical professor of Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine and Attending Psychiatrist Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, The Haven, Addiction and Recovery Units at NewYork Presbyterian-Westchester Behavioral Health Center.

Mary Brous, MSN, BSN is director of Nursing at NewYork Presbyterian-Westchester Behavioral Health Center.

Kevin Cantwell, RN is administrative senior Staff Nurse at NewYork Presbyterian-Westchester Behavioral Health Center.

Mark J Russ, MD is professor of Clinical Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine and Vice Chair of Clinical Programs and Medical Director of NewYork Presbyterian-Westchester Behavioral Health Center.

Patricia Fogarty Mack, MD, FASA is associate professor of Clinical Anesthesiology, Vice Chair for Patient Safety and Quality Improvement and Director of Non-Operating Room Anesthesiology at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. The role of ECT in Suicide Prevention. J ECT 2014; 30: 5-9.

- Espinoza R, Kellner CH, McCall WV. ECT during COVID-19; an essential medical procedure-maintaining service viability and accessibility. J ECT. 2020;78-79.

- https://dev2.apsf.org/news-updates/perioperative-considerations-for-the-2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19/ Accessed March 18, 2020

- Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, et al. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. In J Oral Sci. 2020; 12: 9.

- https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/march/ada-adds-frequently-asked-questions-from-dentists-to-coronavirus-resources (Accessed March 28, 2020)6. Kampf G, Todt D. Pfaender S, et al. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2020; 104, 246-251.

- Flexman Alana, Abcejo Arnoley, Avitisian Rafi, et al. Neuroanesthesia Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology. 2020;32:2.

- https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2020/04/asa-and-apsf-joint-statement-on-perioperative-testing-for-the-covid-19-virus.

Articles

Articles