Health care providers can respond to emergencies more efficiently by using operating room (OR) emergency manuals (EMs) because EMs allow rapid management with established guidelines.1

A simulation-based randomized trial demonstrated that during a series of surgical-crisis scenarios, 23% of critical actions were missed when checklists were not used vs. only 6% were missed when OR crisis checklists were used.2 For those reasons, EMs are being increasingly adopted and implemented in operating rooms.1

EMs have also been adopted internationally, including in China. Three anesthesia EMs have been translated into Chinese: Stanford Operating Room Emergency Manuals, Harvard Ariadne Lab Operating Room Crisis Checklists, and Society for Pediatric Anesthesia Pedicrisis Critical Events Cards. The successful EMs implementation report in China was published in the APSF Newsletter last year.3 (https://dev2.apsf.org/newsletters/html/2016/Oct/06_ChinaManual.htm).

Goldhaber-Fiebert and colleagues suggested in a recent study that simulation training is a powerful tool to improve clinical EM implementation and usage.1 Multidisciplinary simulation training is still lacking in China. Recently, several events were organized to stimulate multidisciplinary simulation training. Emergency manuals simulation training was promoted by using a range of educational modalities including (1) lecture, (2) simulation workshop, (3) simulation demonstration in a meeting, and (4) simulation training competition.

Workshop

An Anesthesia Crisis Resource Management Workshop was organized by the Department of Anesthesiology, Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, China, on May 13–14, 2017 (Figure 1). The goal of this workshop was to introduce the participants to why, how, and when to use EMs and to use Emergency Manuals as a resource for both education and clinical care. The participants could become qualified teachers to organize and teach simulation in their institutes (train the trainers). Training on why, when, and how to use EMs is essential for the effective adoption and implementation of EMs in any facility.

Figure 1. Participants and faculty at the Anesthesia Crisis Resource Management Simulation Workshop, Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing, China.

The participants registered for a two-day simulation training session and all participants attended interactive lectures regarding the use of an emergency manual in the perioperative environment. Then they were divided into two groups. One group used a full human patient simulator (high fidelity) mannequin, SimMan Essential (Laerdal, Wappingers Falls, NY, USA). The other group used CPR mannequin (low fidelity) and an iPad to display the simulated vitals generated by the SimMon (Castle Andersen ApS). The two groups were switched after two hours and each team participated in two scenarios. Each scenario lasted 15–20 minutes and was followed by a debriefing session. On Day 2, the participants were trained to write simulation training scripts. The workshop faculty included Yi Feng, Haiyan An, Hui Ju, Hong Zhang, Ran Zhang, Shuo Guan, Shuo Liu, Jie Zhang, and author Jeffrey Huang.

The workshop received very positive feedback from the participants. The survey indicated that participant satisfaction with the workshop was high. They all understood the importance of simulation training. The participants reported that they will organize simulation training in their hospitals.

Simulation Demonstration

Training on why, when, and how to use EMs can be demonstrated by a group of anesthesia educators in an anesthesia conference. Demonstration-based methods have the advantages of simulation with lower expense. Expert demonstration appears similar to simulation and is superior to didactics for teaching incoming interns teamwork skills.4 Watching a videotaped simulation case was similarly effective to participating in a simulation.4 Development of demonstration-based training for teaching crisis resource management might be an effective and cost-efficient way of implementing emergency manuals.

An EM simulation demonstration was part of the program at a regional anesthesia meeting. A group of anesthesiologists from the Department of Anesthesia, Xiangyang Central Hospital, formed the “simulation education team.” They created scenarios from prior real life events. The team modified these scenarios after simulation practice to improve them for broad-based provider use.

The simulation education team rehearsed scenarios several times to ensure that no element was omitted, all required resources were available, and that it could run smoothly and realistically.

Figure 2. The 2017 Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Perioperative Management Seminar and the Anesthesia Crisis Management Simulation Workshop was held in Xiangyong, Hubei, China.

On May 6, 2017, the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Perioperative Management Seminar and the Anesthesia Crisis Management Simulation Workshop was held in Xiangyong, Hubei, China (FIgure 2). The team, led by Mingqiang Li, Fan Ye, Jianfeng Zhang, and the author, performed live in front of a large group of participants. They engaged in four OR crisis scenarios. At the end of each scenario, the experts were invited to evaluate their performance. The audience was welcome to make comments or suggestions. The simulation demonstrations were well received and highly praised by the audience.

Simulation Training Competition

Figure 3. The 1st place winners with judges (left to right: Wenqi Huang, Jeffrey Huang, Hongtao Liang, Zhou Cheng, Wuhua Ma) at the Operating Room Emergency Manuals Simulation Training Competition in Zhongshan, Guangdong, China

Multidisciplinary training in emergency manuals simulation training has been slowly implemented due to many practical issues, such as scheduling conflicts, lack of a training facility, and lack of trained instructors. Simulation competition has been demonstrated as an effective educational intervention.5 In an effort to stimulate a multidisciplinary team training for emergency manuals implementation, an Operating Room Emergency Manuals Simulation Training Competition was launched as a pilot program in Zhongshan City, Guangdong, China. The competition invitation was sent to each local hospital by the Zhongshan City Society of Anesthesiology. The organizing committee was led by Binfei Li and Chunyuan Zhang. The hospital was required to send a video clip of simulation training for evaluation. The top scoring teams advanced to the final round, a half-day event where multidisciplinary teams from seven local hospitals competed against each other. The finals were judged by a panel of experts from outside Zhongshan City. Each team wrote their own simulation scenario, and rehearsed their scenario prior to the competition. Content was focused on crisis resource management skills by using cognitive aids (Stanford Operating Room Emergency Manuals).

The judges’ panel was composed of three anesthesiologists (Wenqi Huang, Wuhua Ma, and the author). The scoring tool design was based on ANTS (Anesthetist Non-Technical Skills). According to total scores of three judges, the teams were awarded 1st, 2nd, and 3rd places (Figure 3). Every team in the final round received an award. The seven hospitals in the final round included People’s Hospital of Zhongshan, Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Zhongshan, Boai Hospital of Zhongshan, Zhongshan Torch Development Zone Hospital, Huangpu People’s Hospital of Zhongshan, Zhongshan Dongshen Hospital, and Zhongshan Banfu Hospital (Figure 4).

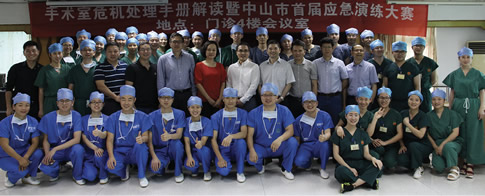

Figure 4. The Operating Room Emergency Manuals Simulation Training Competition was organized in Zhongshan, Guangdong, China. The participating teams included People’s Hospital of Zhongshan, Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Zhongshan, Boai Hospital of Zhongshan, Zhongshan Torch Development Zone Hospital, Huangpu People’s Hospital of Zhongshan, Zhongshan Dongshen Hospital, and Zhongshan Banfu Hospital.

To our knowledge, this competition is the first of its kind in China. The organizing committee received strong positive feedback from participants and faculty involved. The event has served as a catalyst to stimulate the participants to organize simulation training for implementation of operating room emergency manuals. Plans for the continued growth of this project are under way.

Conclusion

Simulation workshops, simulation demonstrations in a meeting, and simulation training competitions are potential approaches to promote multidisciplinary simulation training and implementation of EMs. Successful implementation of EMs in China depends on all-level leadership support, individual provider participation, frequent EMs review, and simulation training.

Dr. Huang is Vice Chief of Quality, Anesthesiologists of Greater Orlando, a Division of Envision; Associate Professor at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine; serves on the APSF Committee on Education and Training; and on the ASA Committee on International Collaboration.

Dr. Huang has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Goldhaber-Fiebert SN, Pollock J, Howard SK, et al. Emergency manual uses during actual critical events and changes in safety culture from the perspective of anesthesia residents: A pilot study. Anesth Analg 2016;123:641–9.

- Arriaga AF, Bader AM, Wong JM, et al. Simulation-based trial of surgical-crisis checklists. N Engl J Med 2013;368:246–53.

- Huang J. Implementation of emergency manuals in China. APSF Newsletter 2016;31:43–45.

- Semler MW, Keriwala RD, Clune JK, et al. A randomized trial comparing didactics, demonstration, and simulation for teaching teamwork to medical residents. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:512–9.

- Damon Dagnone J, Takhar A, Lacroix L. The Simulation Olympics: a resuscitation-based simulation competition as an educational intervention. CJEM 2012;14:363–8.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF