当患者接受非心脏大手术后重返麻醉后监护室时,家属认为他们已经平安度过围手术期中最危险的环节。然而,这种观点并不正确。术后 30 天死亡率比术中死亡率高 100 倍以上。1,2事实上,如果将术后一个月视为一种疾病,则其将成为美国的第三大死亡原因。3

当患者接受非心脏大手术后重返麻醉后监护室时,家属认为他们已经平安度过围手术期中最危险的环节。然而,这种观点并不正确。术后 30 天死亡率比术中死亡率高 100 倍以上。1,2事实上,如果将术后一个月视为一种疾病,则其将成为美国的第三大死亡原因。3

四分之三的术后死亡发生在初次住院期间,也就是说,在我们最高级别医疗机构的直接医疗照护下发生的死亡。4两种最常见且类似的非心脏手术后 30 天死亡原因是大出血和心肌损伤。5,6

心肌损伤

依据第 4 次统一定义,心肌梗死 (Myocardial infarction, MI) 是通过肌钙蛋白升高和心肌缺血的症状或体征来定义的。7非心脏手术后的心肌损伤(Myocardial Injury after Non-Cardiac Surgery, MINS) 是通过疑似缺血性肌钙蛋白升高来定义的,并与 30 天8和一年期9死亡率高度相关。MINS 包括心肌梗死和不符合心肌梗死定义的其他缺血性损伤。

围手术期心肌损伤通常是一起 2 类事件,大部分由供需不平衡引起。因此,MINS 和围手术期心肌梗死不同于非手术性梗死(这种梗死通常由斑块破裂引起)。需要注意的是,围手术期心肌事件导致的死亡率高于非手术性梗死导致的死亡率 — 因此需要高度重视。10,11

肌钙蛋白筛查

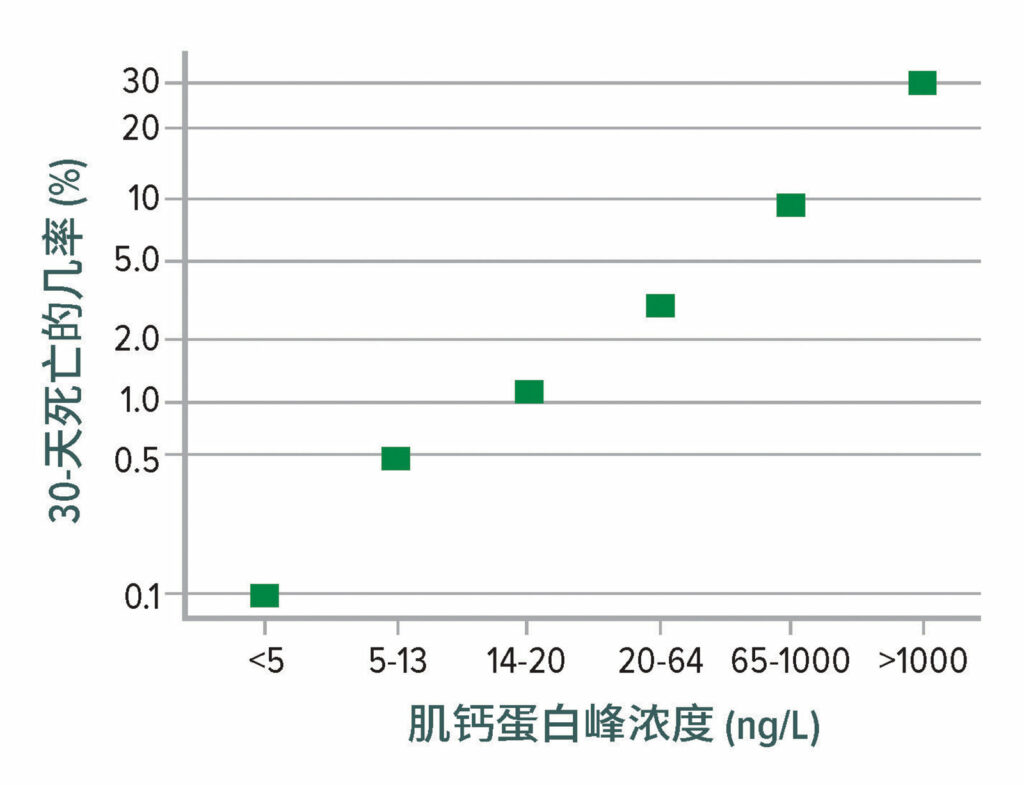

超过 90% 的 MINS 和 MI 发生在术后头两天,超过 90% 的病例无症状12。虽然人们很容易将无症状的肌钙蛋白升高处理为“肌钙蛋白病”,但无症状和有症状的死亡率几乎是一样高(图 1)。因此,MINS 应像典型有症状梗死那样严肃对待。

图 1:30 天死亡率与术后高敏感性肌钙蛋白 T 浓度峰值的关系。死亡率 从 0.1% (肌钙蛋白 T 浓度 < 5 ng/L)显著增至 30% (当肌钙蛋白 T 浓度超过 1,000 ng/L 时)。

数据来自 Vision Study Investigators 的编写委员会:在接受非心脏手术的患者中,术后高敏感性肌钙蛋白水平与心肌损伤和 30 天死亡率的相关性。12

本图改编自参考文献 12 中提供的数据。

如果不进行常规肌钙蛋白筛查,则多数心肌损伤将会被漏诊。合理的策略是在术前和术后头三天测定肌钙蛋白。根据不同的分析方法和分析类型,MINS 的阈值有所不同:

- 非高敏感性(第四代)肌钙蛋白 T ≥ 0.03 ng/ml4;

- 2.高敏感性肌钙蛋白 T ≥ 65 ng/L;或高敏感性肌钙蛋白 T = 20–64 ng/L,且与基线相比增高 ≥ 5 ng/L12;

- 3.高敏感性肌钙蛋白 I(Abbott 分析方法 [Abbott Park, IL])≥ 60 ng/L13;

- 4.高敏感性肌钙蛋白 I(Siemens 分析方法 [Munich, Germany])≥ 75 ng/L(Borges,未公开发表);

- 肌钙蛋白 I(其他的分析方法)至少是当地第 99 个百分位值的两倍;

- 6.对于术前高敏感性肌钙蛋白浓度超过第 2-5 项中相关阈值 80% 的患者,至少增加了 20%。

低血压

MINS 和 MI 均与许多不可修改的基线特征(包括年龄、糖尿病和心脏血管病史等)密切相关。大规模随机试验 (n=7,000–10,000) 显示,MI 不能通过 β-阻断剂来安全预防,14以避免因氯压定16或阿司匹林17 而产生一氧化二氮15 。在近期开展的一项大规模试验中, 七分之一的MINS患者在术后 17 个月内发生了一起重大血管事件(多半是心梗复发)。11

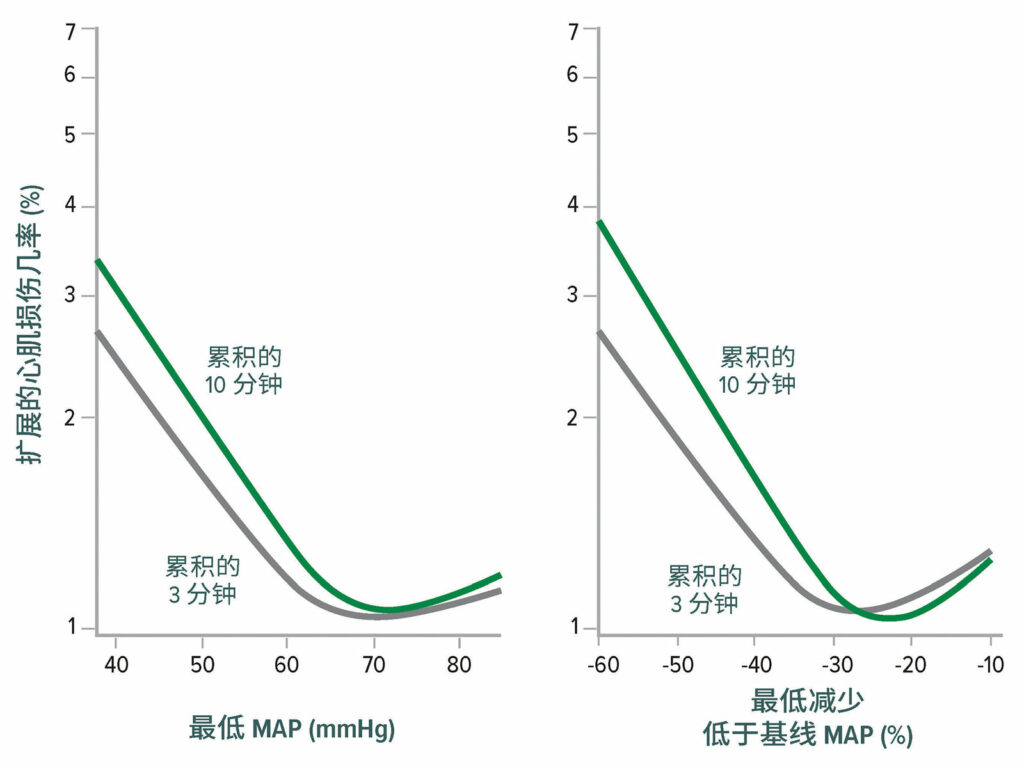

术中低血压与 MINS 和 MI 相关,其风险阈值为平均动脉压 (Mean Arterial Pressure, MAP) ≈ 65 mmHg(图 2)。18,19 术后低血压也与心肌梗死有关,与术中低血压无关(图 3)。20,21

图 2:非心脏手术后心肌损伤的最低平均动脉压 (Mean Arterial Pressure,MAP) 阈值。左图显示了维持 3 分钟和 10 分钟的最低累积平均动脉压绝对值与心肌损伤之间的关系。右图显示了维持 3分钟 和 10 分钟的最低累积平均动脉压相对值与心肌损伤之间的关系。两个图均为对基线特征进行调整后的多变量逻辑回归分析。18

经许可复制和修改。Salmasi V, Maheshwari K, Yang D, Mascha EJ, Singh A, Sessler DI, Kurz A. Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis.Anesthesiology.2017;126:47–65.

图 3:围手术期三个时段 30 天心肌梗死和死亡率的平均相对影响的优势比:术中、术后当天以及术后四天。通过 Bonferroni 校正,对多重比较的 CI 进行了调整。相应地,如果 P<0.017 (0.05/3),则判定平均相对影响有统计学意义。正方形表示优势比,短线条表示 CI。POD = 术后日。20

经许可复制和修改。Sessler DI, Meyhoff CS, Zimmerman NM, Mao G, Leslie K, Vasquez SM, Balaji P, Alvarez-Garcia J, Cavalcanti AB, Parlow JL, Rahate PV, Seeberger MD, Gossetti B, Walker SA, Premchand RK, Dahl RM, Duceppe E, Rodseth R, Botto F, Devereaux PJ.Period-dependent associations between hypotension during and for four days after noncardiac surgery and a composite of myocardial infarction and death: a substudy of the POISE-2 trial.Anesthesiology.2018;128:317–327.

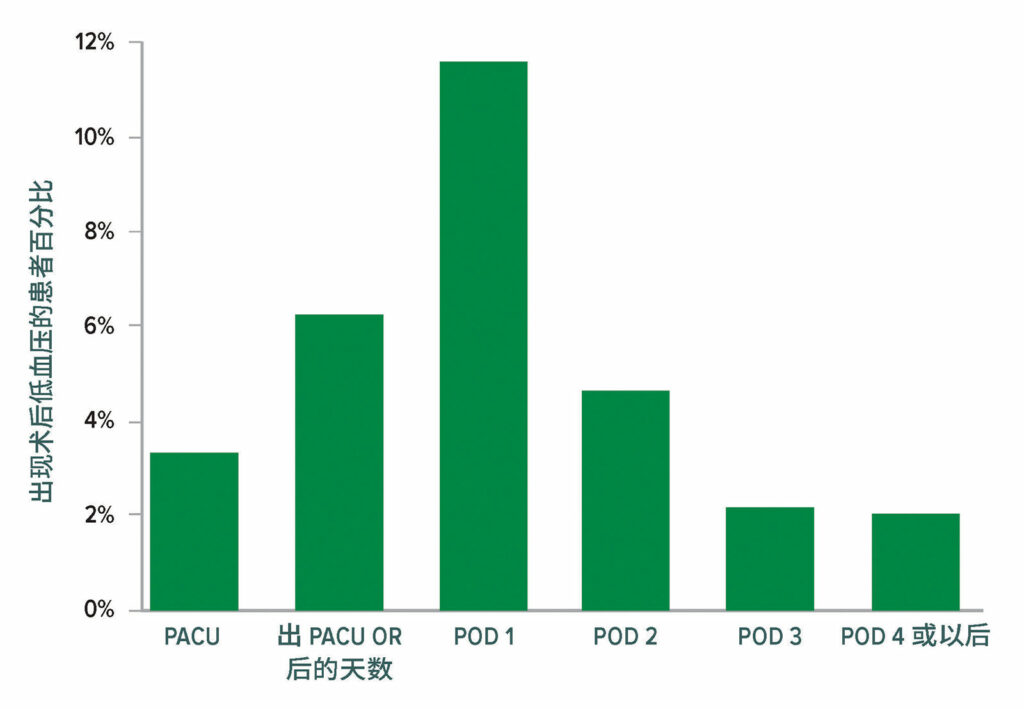

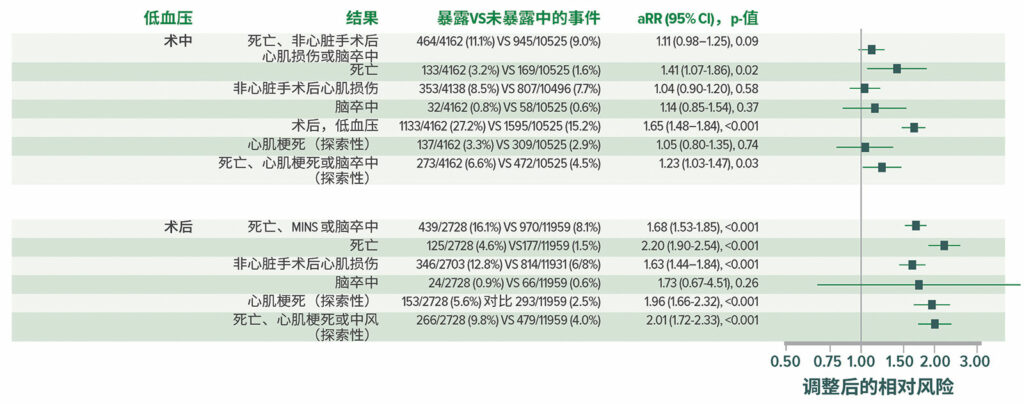

来自 VISION 队列的结果显示,术后低血压很常见(图 4),并与重大血管事件密切相关。与术中低血压相比,术后低血压与心肌梗死和/或死亡的相关性更强(图 5)。22 围手术期低血压还与中风有关,14,22-25尽管这种相关性并不一致。26

图 4:有临床意义的低血压(收缩压 < 90,并立即进行干预)。总计有 2,860/14,687 名患者在接受手术后至少经历了一起有临床意义的低血压事件;其中有 2,728 (95.4%) 名患者在术后3 天内经历了一起低血压事件。OR = 手术室;PACU = 麻醉后监护室。22

经许可复制和修改。Roshanov PS, Rochwerg B, Patel A, et al.Withholding versus continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers before noncardiac surgery: an analysis of the vascular events in noncardiac surgery patients cohort evaluation prospective cohort.Anesthesiology.2017;126:16–27.

图 5:在所有 14,687 名患者中,低血压和术后死亡和血管事件之间调整后的相关性。aRR = 调整后的相对风险。22

经许可复制和修改。Roshanov PS, Rochwerg B, Patel A, et al.Withholding versus continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers before noncardiac surgery: an analysis of the vascular events in noncardiac surgery patients cohort evaluation prospective cohort.Anesthesiology.2017;126:16–27.

其他因素

最近有两项研究发现术后贫血与心肌损伤27和心肌梗死28之间有明显的强相关性,即使是在调整了基线患者特征和术前贫血以后,情况也是如此。相反,高达 100 次/min 的心率和高达 200 mmHg 的收缩压并不是术后心肌损伤的重要危险因素。29 综合医院低氧血症是很常见的、病情严重并且持续时间较长30;不过,仍然不清楚低氧血症是否会导致心肌损伤。一旦低血压和低氧血症在院内同时发生 – 这种情况可能会引发罕见的供血需求性损伤。

急性肾损伤

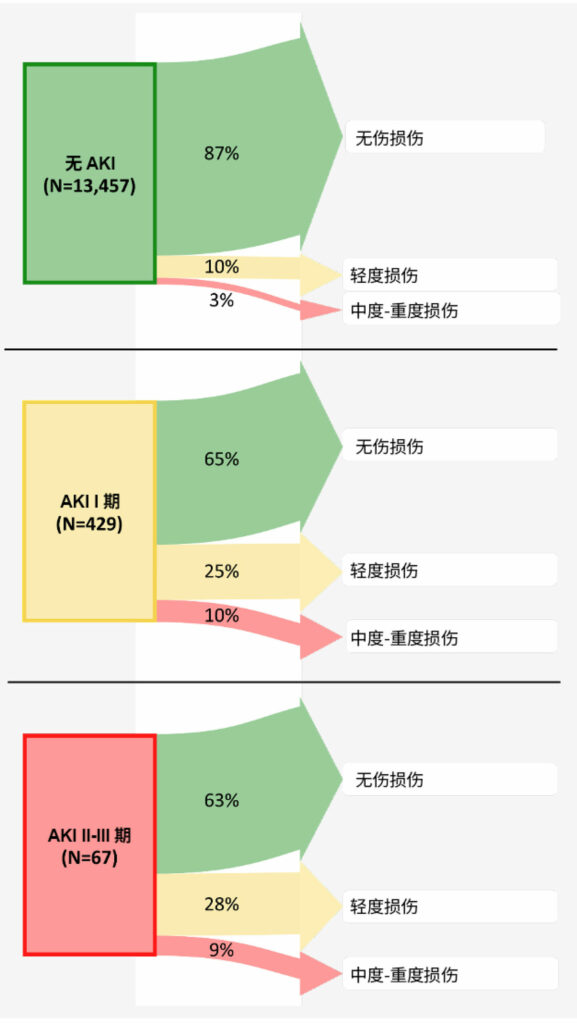

图 6:术后 1-2 年的肾脏结果 – 根据术后急性肾损伤分期。箭头宽度表示来自每个暴露组(有每种长期肾脏损害分期的)的患者百分比。37四分之一有 I 期术后肾脏损害(肌酐增高 ≥ 0.3 mg/dl ,或为基线水平的 1.5–1.9 倍)的患者在其后 1-2 年仍有轻度损伤,10% 的患者甚至有更高分期的损伤。因此,三分之一的 I 期肾损伤患者在术后 1-2 年发生了肾损伤。所以,与没有术后肾损害的患者相比,术后 I 期肾损害的患者发生长期肾损害的让步比 (95%CI) 为 2.3 (1.8, 2.9) 。因此,我们得出结论,在非心脏手术康复的成人中,即使术后血浆肌酐轻度升高(对应于 I 期肾损伤),也与术后 1-2 年肾功能恶化相关,所以应将其视为具有临床意义的围手术期结局。

经许可复制和修改。Turan A, Cohen B, Adegboye J, Makarova N, Liu L, Mascha EJ, Qiu Y, Irefin S, Wakefield BJ, Ruetzler K, Sessler DI.Mild acute kidney injury after noncardiac surgery is associated with long-term renal dysfunction: a retrospective cohort study.Anesthesiology.2020;132:1053–1061.

非心脏手术后,新发急性肾损伤 (Acute Kidney Injury, AKI) 十分常见,患者中的 2–3 期急性肾损伤发生率高达 1%,31 若囊括 1 期 AKI 患者,其发生率则高达 7.4%。32 当前还没有可靠的手段来预测AKI。33 AKI 的低血压风险阈值与心肌损伤的低血压风险阈值相似或略高,可能是由于肾脏的高代谢速率所致。18,32,34

值得注意的是,在更为严格的 MAP 临界值下 (< 55 mmHg),<5 分钟低于该血压值会导致 AKI 风险升高 18%。34 其他分析报告了类似的关联。35 综上所述,这些研究表明围手术期低血压的程度和持续时间与 AKI 之间有密切关联,因此,在对低血压进行量化时,有必要考虑低血压的持续时间和偏离程度。

围手术期 AKI 的影响超过了住院治疗。在囊括1,869 名患者的观察性队列中,研究围手术期 AKI 与 1 年期死亡率的相关性,AKI 与调整后的死亡风险比为 (3) 相关。36 最后,我们注意到,即使是轻度 AKI 也会产生长期的影响:37% 的顽固性 1 期 AKI 或在非心脏手术后 1-2 年恶化(图 6)。37

谵妄

谵妄是心脏手术的一种常见并发症,与心脏手术的发病率和死亡率相关。38-42相关报告显示,非心脏大手术后谵妄发生率约为 10%,当患者的年龄超过 65 岁时,其发生率随患者的年龄增高而增加。43 谵妄的病理生理学是多因素的,但可能包括平均动脉压低于自动调节下限时引起的脑灌注不足。44-46

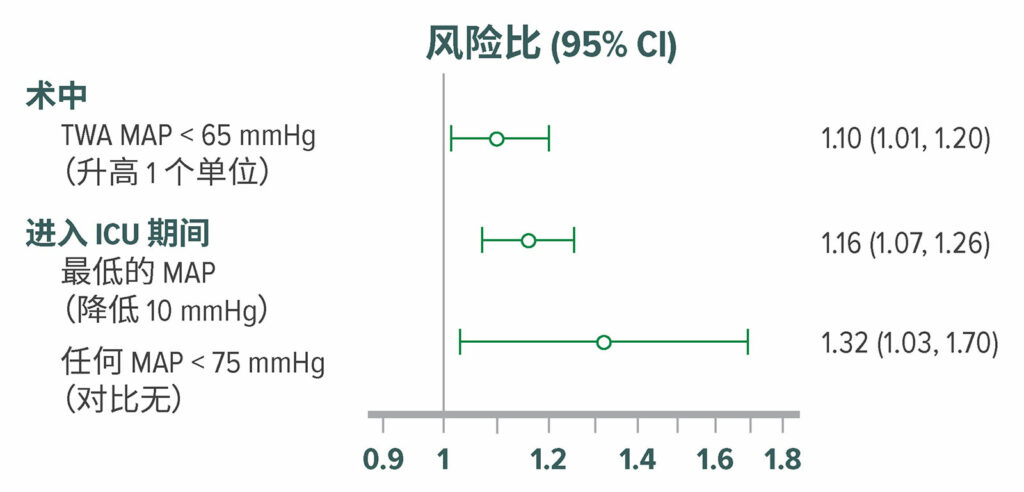

大脑的自动调节阈值仍不清楚,但似乎存在相当大的个体差异,在某些患者中可能会高达 85 mmHg。47,48 与该理论相一致,低血压与谵妄和认知水平下降有关(图 7 ),49-51 尽管这种相关性并不一致。52-54 有限的随机试验数据 (n=199) 显示,低血压可导致谵妄。55

图 7:在直接从手术室进入外科重症监护室的 908 名患者中,调整后的谵妄风险比。使用意识混乱评估方法,按 12 小时间隔,对重症监护室患者的谵妄进行了评估。在外科重症监护室中,316 (35%) 名患者在术后5日内发生了谵妄。术中低血压,MAP <65 mmHg 与较高的术后谵妄发生率显著相关。50 TWA = 时间加权均值。

经许可复制和修改。Maheshwari K, Ahuja S, Khanna AK, Mao G, et al.Association between perioperative hypotension and delirium in postoperative critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort analysis.Anesth Analg.2020;130:636–643.

术后出现谵妄的患者发生长期认知损害的可能性远高于其他患者;56 不过,目前还不清楚这种关联是否具有因果关系。低血压也可能会引发明显的 – 或更为普遍地 – 隐匿性脑卒中,这种情况与谵妄密切相关。57

血压管理

无法通过基线患者特征或外科手术可靠地预测术中低血压。58 目前仍不清楚哪种手段能更好的预防和治疗围术期低血压。术中心脏指数与血压之间几乎没有关联,因此通过维持充足的血容量来预防低血压似乎并不准确。而且,在一项研究中,三分之一的术中低血压发生在麻醉诱导和术中 – 因此显然是麻醉药物,而不是血容量变化引起的。与后续发生的低血压一样,术前低血压也与器官损伤密切相关。59

连续血压监测比与每5分钟进行一次的测量,能检测出更多的低血压患者,60,61 临床医生因此可提早对其进行干预。61 最近制定了一套算法规则,医生可以通过动脉波形来预测将要发生的低血压,这一技术进步令人兴奋不已。62 尽管一项小规模试验称,在该指数的指导下进行管理,低血压发生率较少,63 但一项大规模试验并未发现任何收益。64 这种差异可能源于治疗原则的差异,显然需要开展一项有说服力的临床试验。

血管升压药物(如去氧肾上腺素或去甲肾上腺素)常用于治疗手术期间发生的低血压。去氧肾上腺素是迄今为止在美国最常用的升压药,65 而去甲肾上腺素则是其他国家普遍首选的升压药。去氧肾上腺素是一种纯粹的 α-激动剂,可通过增加全身血管阻力来升高血压,通常伴有心输出量补偿性下降。66 相反,去甲肾上腺素则同时具有强大的 a-肾上腺素能激动作用和弱的 b-肾上腺素能激动活性,可帮助维持心输出量。因此,尽管每种血管升压药血压维持作用相当,67 但去氧肾上腺素可减少内脏血流量和氧气输送。68 临床医生应当避免将去氧肾上腺素用于感染性休克患者。69

尽管使用去甲肾上腺素在理论上具有保护心输出量和内脏灌注的优势,但手术患者改善结果的证据有限。70 因此,去氧肾上腺素和去甲肾上腺素均被广泛用于临床实践,主要基于临床偏好和可获得性。尚无可信证据证明,术中小剂量血管升压药物本身是有害的,为避免使用血管升压药物而置低血压于不顾可能是不明智的。去甲肾上腺素可通过中心静脉导管或外周静脉通路进行给药。71 在近期包含 14,328 名患者的一项研究中,仅有 5 起血管外渗事件,没有任何患者经历局部组织损伤。72

在综合医院,低血压时常发生,且长期存在,有时病情也十分严重。多数围手术期低血压性器官损伤有可能发生在术后,而不是术中。问题在于血压测量通常是间歇性进行。即使间隔4 小时,仍有大约一半的潜在严重低血压事件会被漏诊。73(多数低氧血症在病房间断监测时同样会被漏诊。30)持续监测生命体征是监测和治疗病房低血压的可靠手段。但在此期间,避免在手术当天使用血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂和血管紧张素受体阻断药物会有所帮助,22 只在明确需要时,才会重新开始给予慢性抗高血压药物。

关联性VS因果关系

术中低血压十分常见。根据定义和人群的不同,四分之一或更多的患者手术期间的平均动脉压 < 65 mmHg。术后低血压也很常见,只有大约一半的潜在严重低血压可通过每隔4 小时的常规生命体征监测检出。73 术后低血压通常持续很长时间, 大部分甚至–发展成术后心肌和肾脏损伤。

目前很少有证据表明,低血压与 MINS 和 AKI 之间存在因果关系。但有一项小规模随机试验 (n=292) 证实,预防术中低血压可使重大并发症风险降低 25%,这在生物学上是合理的。74 两项大规模试验将确认观察到的关联性哪些属于因果关系(如有)。POISE-3 (n=10,000, NCT03505723) 试验接近于完成,GUARDIAN (n=6,250, 等待 NCT)试验即将开始。

小结

术中和术后低血压与心肌和肾脏损伤有关。在不同人群中,使用多种阈值和分析方法,均报告有关联性,在调整了已知的基线因素以后,仍然存在这种关联性。(与基线因素的关联性远强于与低血压的关联性,但低血压的不同之处在于它是可以改变的。)低血压和谵妄之间的关联性也有报道,但证据仍然薄弱。

当前几乎没有随机试验数据可用于描述分析观察到的关联性在多大程度上属于因果关系。大规模试验正在进行中,但还需要一段时间才能获得结果。接下来的问题是如何在此期间控制血压。

有两个因素值得特别考虑。第一个因素是低血压与器官损害之间存在因果关系的可能性有多大?当然,许多观察到的关联结果是由于未观察到的混杂因素造成的,或者是预测性的,而不是可以改变的。但似乎也有这样一种可能,即至少有一部分是有因果关系的,因此可以进行干预。第二个需要考虑的因素是使术中平均动脉压维持在 65 mmHg 或某个类似阈值以上的难度有多大?通常,将术中血压维持在明显伤害阈值以上并不难(或费用并不昂贵)。在许多情况下,简单调节麻醉剂给药剂量和熟练的液体管理就足够了。在其他情况下,将需要使用低剂量或中等剂量的血管升压药。尚无可信证据表明,给予低剂量的血管升压药是有害的。预防术后低血压更具挑战性,但延迟重启慢性抗高血压给药至明确需要时的确有所裨益。

血压 – 尤其是低血压的预防 – 是一种可以减少心血管并发症的可变因素。在等待可靠的试验结果之前,应努力避免围手术期低血压。

Daniel I. Sessler(医学博士)是克利夫兰诊所(美国俄亥俄州克利夫兰市)麻醉研究所结果研究部的 Michael Cudahy 教授和主任。

作者是 Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA) 公司的顾问,并在 Sensifree (Cupertino, CA) 和 Perceptive Medical (Newport Beach, CA) 公司咨询委员会任职,且有股东权益。

参考文献

- Li G, Warner M, Lang BH, et al. Epidemiology of anesthesia-related mortality in the United States, 1999-2005. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:759–765.

- Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, et al. European Surgical Outcomes Study group for the Trials groups of the European Society of Intensive Care M, the European Society of A: mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1059–1065.

- Bartels K, Karhausen J, Clambey ET, et al. Perioperative organ injury. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:1474–1489.

- The Vascular Events In Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators: association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2012;307:2295–2304.

- Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation Study Investigators: association between complications and death within 30 days after noncardiac surgery. CMAJ. 2019;191:E830–E837.

- Devereaux PJ, Sessler DI. Cardiac complications in patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2258–2269.

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2231–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. Epub 2018 Aug 25.

- The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators: association between complications and death within 30 days after noncardiac surgery. Can Med Assoc J. 2019;191:E830–E837.

- Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN, Chan MTV, et al. Anzca Clinical Trials Network for the ENIGMA-II Investigators: implication of major adverse postoperative events and myocardial injury on disability and survival: a planned subanalysis of the ENIGMA-II trial. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:1118–1126.

- Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1319–1330.

- Devereaux PJ, Duceppe E, Guyatt G, et al. Dabigatran in patients with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MANAGE): an international, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:2325–2334.

- Writing Committee for the Vision Study Investigators, Devereaux PJ, Biccard BM, Sigamani A, et al. Association of postoperative high-sensitivity troponin levels with myocardial injury and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2017;317:1642–1651.

- Duceppe E, Borges FK, Tiboni M, et al. Association between high-sensitivity troponin I and major cardiovascular events after non-cardiac surgery (abstrract). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75.

- Devereaux PJ, Yang H, Yusuf S, et al. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1839–1847.

- Myles PS, Leslie K, Chan MT, et al. Anzca Trials Group for the ENIGMA-II investigators: the safety of addition of nitrous oxide to general anaesthesia in at-risk patients having major non-cardiac surgery (ENIGMA-II): a randomised, single-blind trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1446–1454.

- Devereaux PJ, Sessler DI, Leslie K, et al. Poise-2 Investigators: clonidine in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1504–1513.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al. Poise-2 Investigators: aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1494–1503.

- Salmasi V, Maheshwari K, Yang D, et al. Relationship between intraoperative hypotension, defined by either reduction from baseline or absolute thresholds, and acute kidney and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:47–65.

- Mascha EJ, Yang D, Weiss S, Sessler DI. Intraoperative mean arterial pressure variability and 30-day mortality in patients having noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:79–91.

- Sessler DI, Meyhoff CS, Zimmerman NM, et al. Period-dependent associations between hypotension during and for four days after noncardiac surgery and a composite of myocardial infarction and death: a substudy of the POISE-2 trial. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:317–327.

- Liem VGB, Hoeks SE, Mol K, et al. Postoperative hypotension after noncardiac surgery and the association with myocardial injury. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:510–522.

- Roshanov PS, Rochwerg B, Patel A, et al. Withholding versus continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers before noncardiac surgery: an analysis of the vascular events in noncardiac surgery patients cohort evaluation prospective cohort. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:16–27.

- Bijker JB, Gelb AW. Review article: The role of hypotension in perioperative stroke. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:159–167.

- Bijker JB, Persoon S, Peelen LM, et al. Intraoperative hypotension and perioperative ischemic stroke after general surgery: A nested case-control study. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:658–664.

- Sun LY, Chung AM, Farkouh ME, et al. Defining an intraoperative hypotension threshold in association with stroke in cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:440–447.

- Hsieh JK, Dalton JE, Yang D, et al. The association between mild intraoperative hypotension and stroke in general surgery patients. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:933–939.

- Turan A, Cohen B, Rivas E, et al. Association between postoperative haemoglobin and myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:94–101.

- Turan A, Rivas E, Devereaux PJ, et al. Association between postoperative haemoglobin concentrations and composite of non-fatal myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality in noncardiac surgical patients: post hoc analysis of the POISE-2 trial. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:87–93.

- Ruetzler K, Yilmaz HO, Turan A, et al. Intra-operative tachycardia is not associated with a composite of myocardial injury and mortality after noncardiac surgery: A retrospective cohort analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019;36:105–113.

- Sun Z, Sessler DI, Dalton JE, et al. Postoperative hypoxemia is common and persistent: a prospective blinded observational study. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:709–715.

- Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Heung M, et al. Development and validation of an acute kidney injury risk index for patients undergoing general surgery: results from a national data set. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:505–515.

- Walsh M, Garg AX, Devereaux PJ, et al. The association between perioperative hemoglobin and acute kidney injury in patients having noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:924–931.

- Whitlock EL, Braehler MR, Kaplan JA, et al. Derivation, validation, sustained performance, and clinical impact of an electronic medical record-based perioperative delirium risk stratification tool. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:1901–1910.

- Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, Garg AX, et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:507–515.

- Sun LY, Wijeysundera DN, Tait GA, et al. Association of intraoperative hypotension with acute kidney injury after elective noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:515–523.

- O’Connor ME, Hewson RW, Kirwan CJ, et al. Acute kidney injury and mortality 1 year after major non-cardiac surgery. Br J Surg. 2017;104:868–876.

- Turan A, Cohen B, Adegboye J, et al. Mild acute kidney injury after noncardiac surgery is associated with long-term renal dysfunction: a retrospective cohort study. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1053–1061.

- Hakim SM, Othman AI, Naoum DO. Early treatment with risperidone for subsyndromal delirium after on-pump cardiac surgery in the elderly: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:987–997.

- Maldonado JR, Wysong A, van der Starre PJ, et al. Dexmedetomidine and the reduction of postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:206–217.

- Royse CF, Saager L, Whitlock R, et al. Impact of methylprednisolone on postoperative quality of recovery and delirium in the Steroids in Cardiac Surgery Trial: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled substudy. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:223–233.

- Shehabi Y, Grant P, Wolfenden H, et al. Prevalence of delirium with dexmedetomidine compared with morphine based therapy after cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial (DEXmedetomidine COmpared to Morphine-DEXCOM Study). Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1075–1084.

- Turan A, Duncan A, Leung S, et al. Dexmedetomidine for reduction of atrial fibrillation and delirium after cardiac surgery (DECADE): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:177–185.

- Gou RY, Hshieh TT, Marcantonio ER, et al. One-year medicare costs associated with delirium in older patients undergoing major elective surgery. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:430–442.

- Hayhurst CJ, Pandharipande PP, Hughes CG. Intensive care unit delirium: a review of diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:1229–1241.

- Daiello LA, Racine AM, Yun Gou R, et al. Postoperative delirium and postoperative cognitive dysfunction: overlap and divergence. Anesthesiology. 2019;131:477–491.

- Pan H, Liu C, Ma X, et al. Perioperative dexmedetomidine reduces delirium in elderly patients after non-cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2019;66:1489–1500.

- Ono M, Arnaoutakis GJ, Fine DM, et al. Blood pressure excursions below the cerebral autoregulation threshold during cardiac surgery are associated with acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:464–471.

- Ono M, Brady K, Easley RB, et al. Duration and magnitude of blood pressure below cerebral autoregulation threshold during cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with major morbidity and operative mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:483–489.

- Feng X, Hu J, Hua F, et al. The correlation of intraoperative hypotension and postoperative cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020;20:193.

- Maheshwari K, Ahuja S, Khanna AK, et al. Association between perioperative hypotension and delirium in postoperative critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:636–643.

- Hori D, Brown C, Ono M, et al. Arterial pressure above the upper cerebral autoregulation limit during cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with postoperative delirium. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:1009–1017.

- Hirsch J, DePalma G, Tsai TT, et al. Impact of intraoperative hypotension and blood pressure fluctuations on early postoperative delirium after non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:418–426.

- Wesselink EM, Kappen TH, van Klei WA, et al. Intraoperative hypotension and delirium after on-pump cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:427–433.

- Langer T, Santini A, Zadek F, et al. Intraoperative hypotension is not associated with postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing general anesthesia for surgery: results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Clin Anesth. 2019;52:111–118.

- Brown CH 4th, Neufeld KJ, Tian J, et al. Effect of targeting mean arterial pressure during cardiopulmonary bypass by monitoring cerebral autoregulation on postsurgical delirium among older patients: A nested randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:819–826.

- Brown CH 4th, Probert J, Healy R, et al. Cognitive decline after delirium in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:406–416.

- Mrkobrada M, Chan MTV, Cowan D, et al. Perioperative covert stroke in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (NeuroVISION): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019; 394:1022–1029.

- Sessler DI, Khan MZ, Maheshwari K, et al. Blood pressure management by anesthesia professionals: evaluating clinician skill from electronic medical records. Anesth Analg. 2021;132:946–956.

- Maheshwari K, Turan A, Mao G, et al. The association of hypotension during non-cardiac surgery, before and after skin incision, with postoperative acute kidney injury: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:1223–1228.

- Naylor AJ, Sessler DI, Maheshwari K, et al. Arterial catheters for early detection and treatment of hypotension during major noncardiac surgery: a randomized trial. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:1540–1550.

- Maheshwari K, Khanna S, Bajracharya GR, et al. A randomized trial of continuous noninvasive blood pressure monitoring during noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:424–431.

- Davies SJ, Vistisen ST, Jian Z, et al. Ability of an arterial waveform analysis-derived hypotension prediction index to predict future hypotensive events in surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:352–329.

- Wijnberge M, Geerts BF, Hol L, et al. Effect of a machine learning-derived early warning system for intraoperative hypotension vs standard care on depth and duration of intraoperative hypotension during elective noncardiac surgery: the HYPE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:1052–1060.

- Maheshwari K, Shimada T, Yang D, et al. Hypotension prediction index for prevention of hypotension during moderate- to high-risk noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:1214–1222.

- Farag E, Makarova N, Argalious M, et al. Vasopressor infusion during prone spine surgery and acute renal injury: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:896–904.

- Ducrocq N, Kimmoun A, Furmaniuk A, et al. Comparison of equipressor doses of norepinephrine, epinephrine, and phenylephrine on septic myocardial dysfunction. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1083–1091.

- Morelli A, Ertmer C, Rehberg S, et al. Phenylephrine versus norepinephrine for initial hemodynamic support of patients with septic shock: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2008;12:R143.

- Reinelt H, Radermacher P, Kiefer P, et al. Impact of exogenous beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation on hepatosplanchnic oxygen kinetics and metabolic activity in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:325–331.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. International Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines C, American Association of Critical-Care N, American College of Chest P, American College of Emergency P, Canadian Critical Care S, European Society of Clinical M, Infectious D, European Society of Intensive Care M, European Respiratory S, International Sepsis F, Japanese Association for Acute M, Japanese Society of Intensive Care M, Society of Critical Care M, Society of Hospital M, Surgical Infection S, World Federation of Societies of I, Critical Care M: Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327.

- Mets B: Should norepinephrine, rather than phenylephrine, be considered the primary vasopressor in anesthetic practice? Anesth Analg. 2016;122:1707–1714.

- Owen VS, Rosgen BK, Cherak SJ, et al. Adverse events associated with administration of vasopressor medications through a peripheral intravenous catheter: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2021;25:146.

- Pancaro C, Shah N, Pasma W, et al. Risk of major complications after perioperative norepinephrine infusion through peripheral intravenous lines in a multicenter study. Anesth Analg. 2019;131:1060–1065.

- Turan A, Chang C, Cohen B, et al. Incidence, severity, and detection of blood pressure perturbations after abdominal surgery: a prospective blinded observational study. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:550–559.

- Futier E, Lefrant JY, Guinot PG, et al. Effect of individualized vs standard blood pressure management strategies on postoperative organ dysfunction among high-risk patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1346–1357.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF