Related Article:

Brain Safety: The Next Frontier for Our Specialty?

What can be done to protect my perioperative brain health?

Sara Lenz Lock, JD, Senior vice president for Policy at the Association of American Retired Persons (AARP), spoke at this year’s American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) annual meeting in San Francisco, CA, on the crucial topic of perioperative brain health and the patient’s concerns regarding the impact of surgery on cognitive function. As a general anesthesiologist who treats a large number of geriatric patients, this question drew one of us (N.K.) to the two-hour, dual-auditorium session hosted by the APSF. A multidisciplinary panel including academic anesthesiologists, researchers, patient engagement and public policy representatives provided some suggestions for management of this increasingly appreciated problem.

Anesthesia professionals and specifically the APSF have a rich patient safety heritage, serving as both leaders and innovators in this field.1 In many respects, safety is the soul of our specialty. This panel upheld that tradition by examining recent developments in the field of perioperative brain health. The themes of the session addressed three overarching questions: (1) What do patients want to know about preserving brain health before upcoming surgery; (2) What can clinicians do to address brain health perioperatively; and (3) How do clinician’s and patient’s goals align with smart public policy?

Brain health is a timely topic. Similar to public interest in the neurotoxicity of anesthesia within the pediatric population,2 it is no surprise that the elderly are interested in the impact of surgery and anesthesia on postoperative cognitive function. The cognitive changes experienced by patients after surgery are not new for anesthesia professionals; we often address concerns about “post-surgical fog” in either pre- or postoperative patient evaluations. Ms. Lock emphasized that patients will turn to their medical providers for answers when their brain health deteriorates. Therefore, patients are likely to inquire about potential risk reduction measures for cognitive dysfunction preoperatively. Similarly, patients might ask about the kind of cognitive effects they are likely to experience after surgery and how long those effects will last.

The conference panelists elucidated the scope of brain health as a patient safety problem, while taking into consideration the demands placed on medical professionals. Dr. Daniel Cole, professor of clinical anesthesiology at UCLA and current APSF vice president, introduced the magnitude of this national problem. He reported that the incidence of post-operative delirium and cognitive dysfunction is between 5-50%3 and costs the health care system approximately $150 billion.4

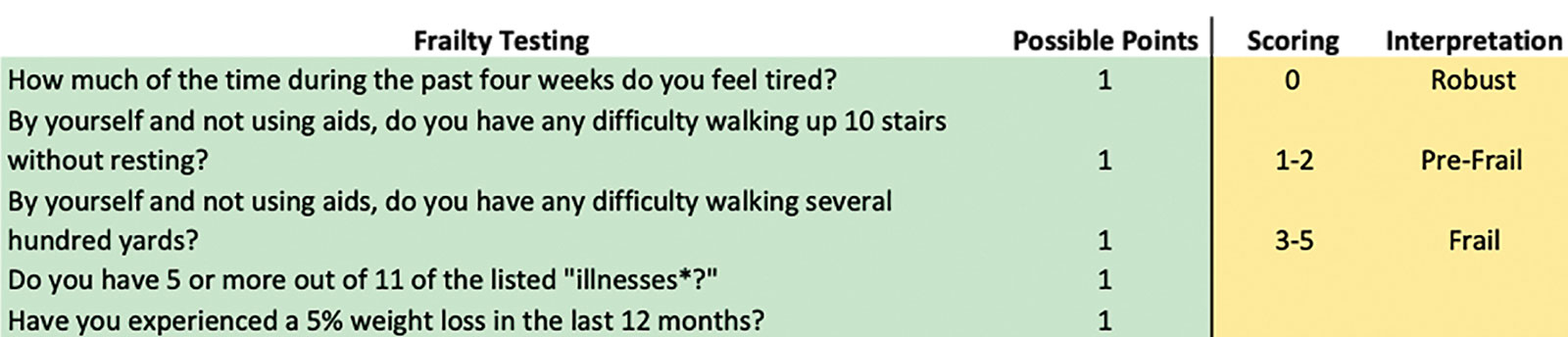

Dr. Deborah Culley, associate professor of anesthesiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, discussed practical screening tools that anesthesia professionals can administer to assess the impact of surgery and anesthesia on cognitive function. These tools include the mini-cognition questionnaire5 (Figure 1) and frailty scoring scale6 (Figure 2). Dr. Carol Peden, professor of clinical anesthesiology at the University of Southern California, encouraged health care professionals to resist the temptation to immediately incorporate the new prevention and intervention data into strict protocols. Rather she suggested employing core change management principles, which focus on engaging all stakeholders including patients, providers, and policy makers. Brain health of the elderly should continue to be examined as a major public health issue.

Figure 1. The Mini-Cog test. There are three steps that include a score for accuracy of “clock drawing” and “three word recall,” resulting in a cumulative score that can increase the detection of cognitive impairment.

Reprinted with permission from Soo Borson, MD. See mini-cog.com for full administration instructions.

Figure 2. A quick test to assess fraility as a predictor of risk for delirium.

*Illnesses include hypertension, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung disease, heart attack, congestive heart failure, angina, asthma, arthritis, stroke and kidney disease

Adapted and reprinted with permission from John Morley, MD.5,6

Dr. Lee Fleisher, chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care at the University of Pennsylvania, illustrated the strategies by which clinicians can engage with geriatric societies and federal partners to help drive clinical culture change. He advocated aligning top-down leadership to promote a strategic agenda around brain health and simultaneously having informal change leaders engaged in clinical practice propagate the strategy leading to a bottom-up cultural change as well. He emphasized working with the geriatric societies to assist in documenting endeavors that address brain health. In this way the impact of brain health efforts will be recognized amongst both clinicians and the public. Finally, Dr. Fleisher also focused on the power of persuasion and urged health care payers to financially incentivize medical professionals to focus on brain health initiatives.

So, where do clinicians go from here in the effort to protect the brain health of patients? Reflections from the audience summarized the challenges to improving perioperative patient brain health (See Audience Generated Reflections).

Audience Generated Reflections

| Patient advocacy societies must maintain an active list of the most frequent and pertinent questions from patients.

Specialty organizations, such as the APSF, need to invest in developing and evaluating screening tools for brain health, including future technologies such as machine learning-based risk assessment. There is a need to establish intraoperative brain monitoring standards linked to improved outcomes that can be implemented directly in our operating rooms (i.e., processed electroencephalogram). |

There is a need to prepare patients with knowledge, active engagement, and medical support to maintain their brain health as they approach major surgery.

For clinicians who treat a larger geriatric population, it was exciting to see the APSF emphasize brain health as a focus of this panel. This year’s APSF panel upheld the long tradition of combining clinical science, research, and public policy to achieve anesthesiology’s foremost mission: patient-centered, safe surgical care.

Dr. Kamdar is currently the director of Quality in the Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine at UCLA Health.

Dr. Fleisher is chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

Dr. Cole is professor of clinical anesthesiology in the Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine at UCLA Health. He is vice-president of the APSF.

The authors have no disclosures as they pertain to this article.

References

- Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA. 1994;272:1851–1857.

- Grady D. Researchers warn on anesthesia, unsure of risk to children. The New York Times. Published December 21, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/26/health/researchers-call-for-more-study-of-anesthesia-risks-to-young-children.html. Accessed November 13, 2018.

- Postoperative delirium in older adults: best practice statement from the American Geriatrics Society – ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1072751514017931?via%3Dihub. Accessed October 29, 2018.

- Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, et al. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:27–32.

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample: Mini-Cog in movies. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:1451–1454.

- Morley JE, Malmstron TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:601–608.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF